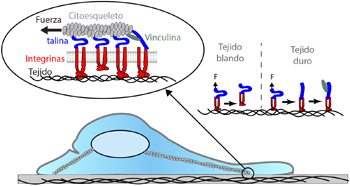

Left: Images of the cell cytoskeleton while applying forces to substrates of different rigidities.

“Most solid tumours are stiffer than normal tissue; for example, breast cancer is usually screened by detecting hard lumps in the breast,” explains junior group leader at IBEC and assistant professor at the University of Barcelona Pere Roca-Cusachs, who led the research. “What’s more, increasing or decreasing tissue stiffness can enhance or impair tumour progression respectively.”

“Just as you would need to sit on or press a mattress to know how soft it is, cells must apply forces to their surroundings to detect stiffness,” says Alberto Elosegui-Artola, first author on the paper. “They do this through different molecules including integrins, which directly bind cells to their surrounding extracellular matrix, and talin, which connects integrins to the cytoskeleton, or body, of the cell.”

Right: Scheme showing how talin and integrins connect the cell cytoskeleton to the surrounding tissue. Depending on whether the tissue is soft or stiff, applied forces will lead first to integrin unbinding or talin unfolding and subsequent vinculin binding.

The researchers discovered that, when cells pull from those molecules while applying forces, if the substrate is stiff, the force unfolds talin, which exposes a binding domain to vinculin, which then binds and triggers the activation of YAP – one of the major players in tumour progression. If the substrate is soft, however, the force is applied slower, causing integrins to unbind from the tissue before talin can unfold, so YAP is not activated.

“This is an important first step that opens the way towards the eventual development of a new strategy that could impair the growth of many types of cancer: breast, lung, prostate, skin, and many others,” says Pere.

The work was funded in part by the Fundació la Marató de TV3.

Source article: Alberto Elosegui-Artola, Roger Oria, Yunfeng Chen, Anita Kosmalska, Carlos Pérez-González, Natalia Castro, Cheng Zhu, Xavier Trepat, Pere Roca-Cusachs (2016). “Mechanical regulation of a molecular clutch defines force transmission and transduction in response to matrix rigidity.” Nature Cell Biology, DOI: 10.1038/ncb3336

—

Check out a video about the work on IBEC’s YouTube channel.

—

IBEC in the Media:

Diario Medico, “La rigidez de los tejidos activa el cancer”

Gaceta Medica, “El oncogen Yap se activa cuando detencta el cancer”

La Rioja, “Descubren como la rigidez de los tejidos activa el cancer”

La Gaceta, “Un grupo de investigadores descubre cómo la rigidez de los tejidos”

El Punt Avui, “Detecten com la rigidésa dels teixits contribueix a desenvolupar el cancer”

El Norte de Castilla, “Descubren como la rigidez de los tejidos activa el cancer”

Canarias7, “La rigidez de los tejidos activa el cancer”

Agencia SINC, “Cómo consigue activar el cáncer la rigidez de los tejidos”

NCYT, “Cómo consigue activar el cáncer la rigidez de los tejidos”

El Economista, “Así es el mecanismo por el que la rigidez de los tejidos activa el cáncer”

La Razón, “Descubren cómo la rigidez de los tejidos activa el cáncer”