A new study led by the Institute for Bioengineering of Catalonia (IBEC) has unveiled the first biomaterial that is not only waterproof but actually becomes stronger in contact with water. The material is produced by the incorporation of nickel into the structure of chitosan, a chitinous polymer obtained from discarded shrimp shells. The development of this new biomaterial, published in Nature Communications, marks a departure from the plastic-age mindset of making materials that must isolate from their environment to perform well. Instead, it shows how sustainable materials can connect and leverage their environment, using their surrounding water to achieve mechanical performance that surpasses common plastics.

Plastics have become an integral part of modern society thanks to their durability and resistance to water. However, precisely these properties turn them into persistent disruptors of ecological cycles. As a result, unrecovered plastic is accumulating across ecosystems and becoming an increasingly ubiquitous component of global food chains, raising growing concerns about potential impacts on human health.

For over a century, we have assumed that, in order to succeed in nature, materials must become inert. This research shows the opposite: materials can thrive by interacting with their environment rather than isolating themselves from it.

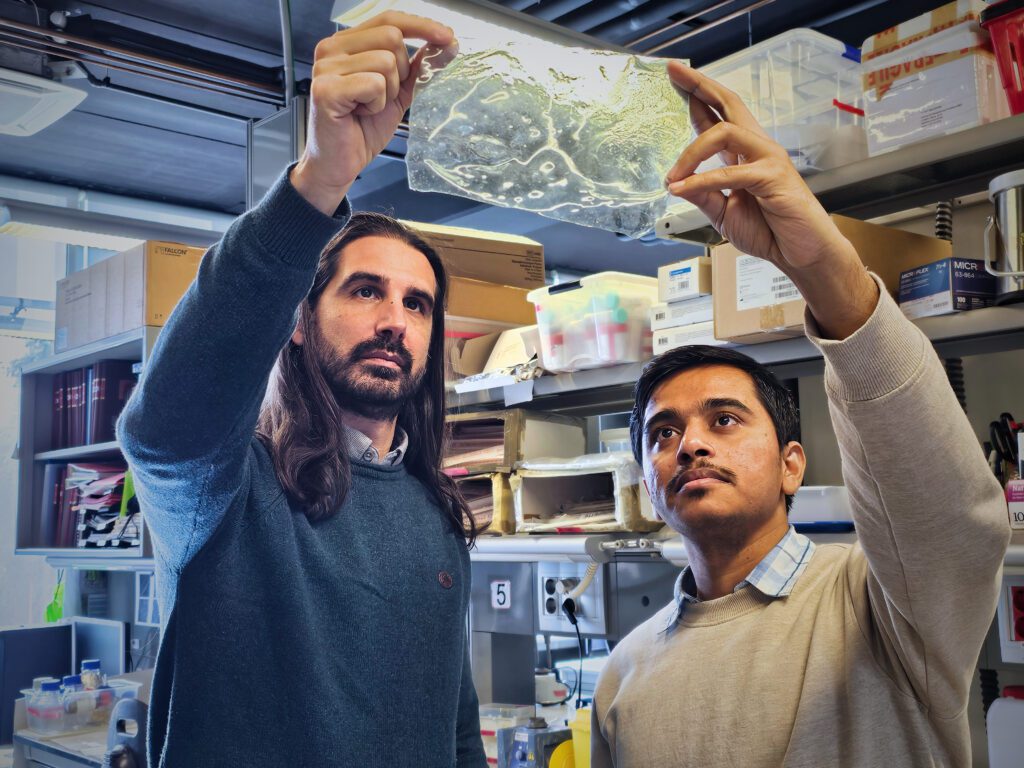

Javier G. Fernández

In an effort to address this challenge, the use of biomaterials as substitutes for conventional plastics has long been explored. However, their widespread adoption has been limited by a fundamental drawback: most biological materials weaken when exposed to water. Traditionally, this vulnerability has forced engineers to rely on chemical modifications or protective coatings, thereby undermining the sustainability benefits of biomaterial-based solutions.

Now, a recent study led by the Institute for Bioengineering of Catalonia (IBEC), in collaboration with the Singapore University of Technology and Design (SUTD), has overturned this paradigm. Inspired by the arthropod cuticle, the researchers adapted chitosan — the second most abundant organic molecule on Earth after cellulose — to create a biointegrated material that resists hydration and increases in strength to values well above those of commodity plastics when wet.

Crucially, the process does not alter the biological nature of chitosan. ‘The material is still biologically pure in the eyes of nature; it remains essentially the same molecule found in insect shells or mushrooms’, explains Javier G. Fernández, ICREA Research Professor at IBEC, principal investigator of the Biointegrated Materials and Engineering group, and leader of the study. This purity enables seamless reintegration into natural ecological cycles.

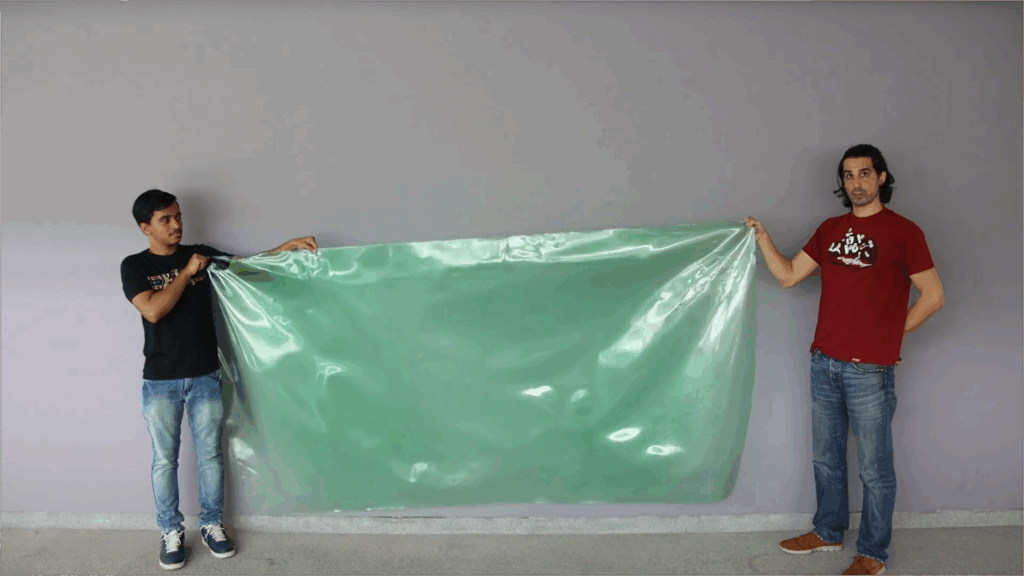

The groundbreaking method, published in Nature Communications, demonstrates the potential for a paradigm shift in manufacturing, with zero-waste production of both consumables and large objects that could meet the global demand for plastic.

A paradigm shift inspired by nature

According to Fernández, most of our current materials, from plastics to engineered biopolymers, are designed to withstand environmental conditions. ‘For over a century, we have assumed that, in order to succeed in nature, materials must become inert,’ he says. ‘This research shows the opposite: materials can thrive by interacting with their environment rather than isolating themselves from it.’

The study was inspired by a serendipitous observation: when zinc is removed from the fangs of the sandworm Nereis virens, the fangs become susceptible to hydration and soften when immersed in water. This finding suggests that metals may play a key role in how natural materials interact with water.

While metals are known to strengthen biological structures, the researchers proposed that they could also control the hydration of chitin-based materials, a natural polymer found in crustacean shells. To test this theory, the team focused on nickel, a naturally occurring trace element that easily interacts with chitin and dissolves in water.

Each year, the world produces an estimated one hundred billion tonnes of chitin, equivalent to three centuries’ worth of plastic production.

Akshayakumar Kompa

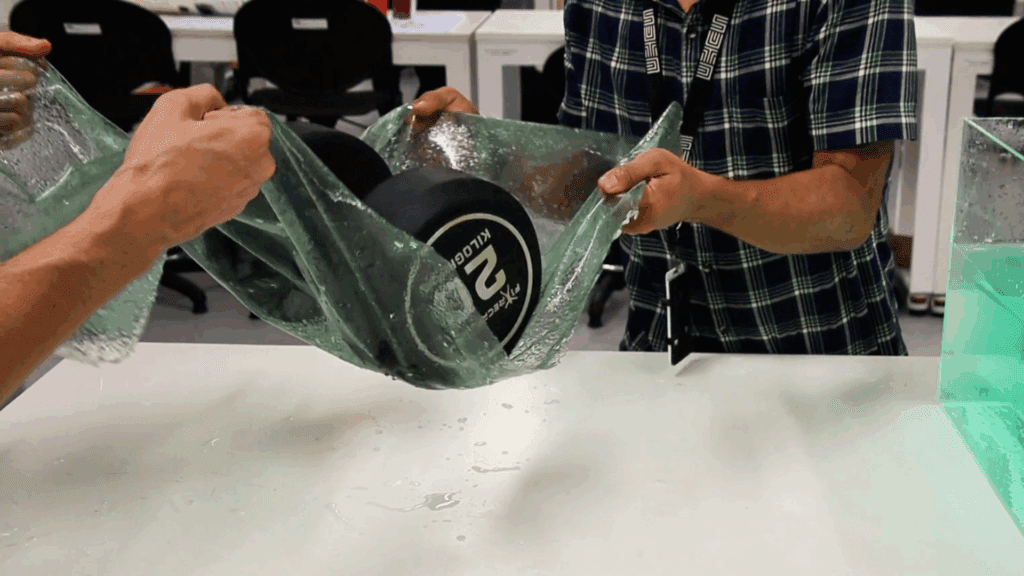

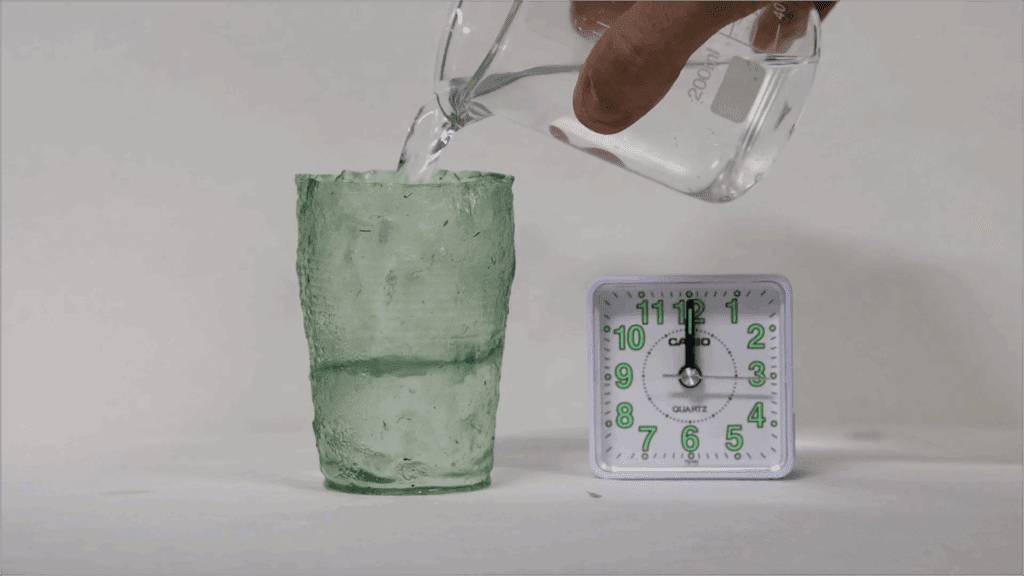

The team incorporated nickel into chitosan — a chitin-derived material obtained from discarded shrimp shells — and processed it into thin films. They report that the material becomes stronger when immersed in water, exhibiting an increase in strength of up to 50% after immersion.

In the new material, water becomes an active structural component. A dynamic network of weak, reversible bonds continuously breaks and reforms due to the mobility of nickel ions and surrounding water molecules. This constant microscopic reconfiguration enables the material to absorb stress and reorganise itself, mirroring the behaviour of natural biological structures.

Fernández summarises this as “a material where being ‘soft’ at the molecular scale actually makes it stronger”.

Zero‑waste production and global scalability

The study also demonstrates a zero‑waste manufacturing process. During the initial immersion of the material in water, the majority of the nickel that does not contribute to structural bonding is released. Rather than discarding this mixture, the team designed a loop in which it becomes the input for producing the next batch of material, achieving a 100% efficiency in the use of nickel.

Our goal is to integrate the production of these materials into the local ecosystem by using whatever form of chitosan is available nearby.

Akshayakumar Kompa

This approach enables the full recovery and reuse of nickel, drastically reducing environmental impact and costs.

Scaling up is equally promising. The authors demonstrate that chitinous polymers are produced on a vast scale in nature, making them ideal candidates for future sustainable manufacturing. ‘Each year, the world produces an estimated one hundred billion tonnes of chitin, equivalent to three centuries’ worth of plastic production,’ states Akshayakumar Kompa, a postdoctoral researcher in Fernandez’s group and the study’s first author.

Moreover, chitosan can be produced locally rather than relying on a single global source. While shrimp shells remain the main industrial source, it can also be obtained through the bioconversion of organic waste, ranging from urban food residues to fungal by-products. “The key is to adapt to local sources,” says Kompa. ‘Our goal is to integrate the production of these materials into the local ecosystem by using whatever form of chitosan is available nearby.’

A promising substitute for plastics

Early applications are expected to emerge in agriculture, fishing gear and packaging, as well as in other water-related uses, where there is an urgent need for biodegradable, water-resistant materials.

While the team has prioritised industrial scalability and cost, focusing initially on agricultural applications, both nickel and chitosan are individually approved by the FDA for certain medical uses. Consequently, the findings could also pave the way for applications in the medical field, including waterproof coatings for biomaterials.

Furthermore, the material’s ability to form watertight containers, demonstrated in the study using cups and large sheets, highlights its potential to replace certain single-use plastics.

The authors emphasise that nickel is probably not the only molecule capable of producing this phenomenon. Now that the principle is understood, other combinations may broaden the possibilities of strengthening biomaterials with water.

“This is the first study. Now that we know this effect exists, we and others can search for new materials and new ways to achieve it,” notes Fernández.

This discovery represents a shift in mindset away from the plastic age. Rather than forcing biological molecules to behave like synthetics, the IBEC team embraces the logic of natural systems: dynamic structures, regional production, ecological integration, and zero waste.

For Kompa and Fernández, the message is clear: to build a sustainable future, we must design materials that work with the environment, not isolating form it.

Referenced paper:

Akshayakumar Kompa and Javier G Fernandez. Stronger when wet: Aquatically robust chitinous objects via zero-waste coordination with metallic ions. Nature Communications (2026). DOI: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-026-69037-4